In the new research, described in the journal Science Translational Medicine on Wednesday, scientists injured two rat molars, side by side, and then administered the laser treatment to only one tooth. They saw roughly twice the amount of regeneration that occurred on the untreated tooth, after a single, five-minute laser treatment.

“There have been lots of anecdotal reports that laser treatment can trigger regeneration, but it has been unclear how reproducible it is,” said David Mooney, a professor of bioengineering at Harvard who led the work.

The researchers also began to untangle how the laser treatment worked, by triggering a molecular chain of events within the tissue. Those insights suggest, more broadly, that stem cell therapies may not always require creating cells and grafting them back into the body, but could also include triggering cells in the body to form new tissue using external stimulation.

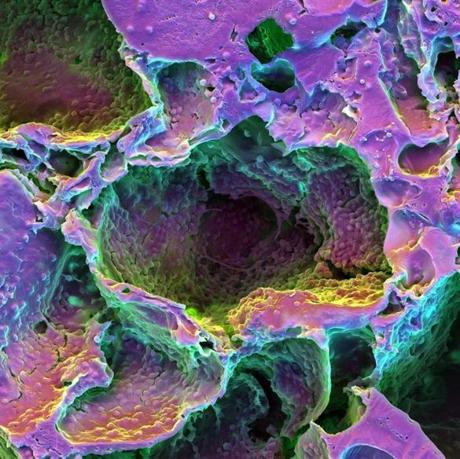

The portion of the tooth that grew back is called dentin -- a mineralized tissue that forms a layer between the pulp and the outer enamel of the tooth. The new dentin had a different structure than in naturally-occurring teeth, which may be a problem to be refined and studied further.

Mooney said that the basic science described in the paper has the potential to take a relatively short path into the dentist’s office because the treatment can be localized and doesn’t require a powerful laser. The low-power laser the researchers used appeared to trigger no immune response or destruction of tissue. Instead, it caused cells to create molecules called reactive oxygen species that subsequently triggered a boost in a protein called TGF-beta1, which is known to activate stem cells.

Mooney said that one of the scientists who led the work, Praveen Arany, has since moved on to work at the National Institutes of Health, and is focused on translating these insights into a therapy that could be tested in people, as an alternative way to cap teeth and prevent root canals, for example, or to decrease tooth sensitivity to extremes of temperature.

Mooney is also interested in whether a similar approach could be used to stimulate stem cells to regrow other types of tissue.

Dr. Jonathan Garlick, director of the Center for Integrated Tissue Engineering at the Tufts University School of Dental Medicine, who was not involved in the research, said it was a powerful proof-of-concept. Now that it is clear that the laser can trigger regrowth of tooth tissue, he said, it will simply be a matter of refining the technique and learning how to use it to regrow the tissue appropriately -- and making sure that it doesn’t cause any side effects. He added that the technique could eventually find wide use.

“I think it’s very relevant directly in a variety of different tissues that require stimulation and activation of healing and repair -- such as chronic foot ulcers in diabetic patients, bone healing, and bone regeneration,” Garlick said. “I think this has broad applications.”